Washita oilstones are used by woodworkers around the world and they all come from a small area east of Hot Springs in Arkansas, USA.

Origins

Washita, and the closely related Arkansas stone, are both forms of a rock geologists call Novaculite. As this research shows, Novaculite was used by Indians to make tools long before America was discovered by Europeans.

There is evidence of Indians living and working in the Hot Springs area for thousands of years, but it was not until the early part of the 19th Century that we find reports of Novaculite being used commercially as an abrasive. Henry Schoolcraft’s 1819 book on the geology of Missouri and Arkansas says:

“A quarry of this mineral (novaculite), three miles above the Hot Springs of Washita, has often been noticed by travellers for its extent and excellency of its quality. A specimen now before me, is of a grayish white colour, partaking a little of green, translucent in an uncommon degree, with an uneven and moderately glimmering fracture, and susceptible of being scratched by a knife. Oil stones, for the purpose of honing knives, razors and carpenter’s tools, are occasionally procured from this place, and considerable quantities have been lately taken to New-Orleans. It gives a fine edge, and is considered equal to the Turkish oil stone. Henry R. Schoolcraft, A View of the Lead Mines of Missouri, etc. (New York, 1818)

Later authors credit Schoolcraft with identifying the stone as a type of Novuculite but in in a paper included in the book he published several decades later, he is at pains to point out that he regards it as a particular type of stone in its own right:

Sedimentary Quartz—Schoolcraftite: This mineral occurs three miles from the Hot Springs of Washita. It is of a grayish-white color, partaking a little of green, yellow, or red; translucent in an uncommon degree, with an uneven and moderately glimmering fracture, and susceptible of being scratched with a knife. Oil stones for the purpose of honing knives, razors, or tools, are occasionally procured from this place… It has been improperly termed, heretofore, “novaculite.” Scenes and Adventures in the Semi-Alpine Region of the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, 1853

Apparently his suggestion to rename it Schoolcraftite did not catch on and the term novaculite has stuck to this day. A later account by David Day (1860) distinguishes two types of stone, Arkansa and “Ouachita” (Washita being an alternative spelling of this name):

(the Hot Spring) ridge or mountain as it is usually called – though it is only two hundred and fifty feet above the Hot Spring Valley – is made up of the most beautiful variety of Novaculite (“Ouachita oilstone or Arkansas whetstone”) equal in whiteness closeness of texture and subdued waxy lustre to the most compact forms and white varieties of Carrara marble and though of an entirely different composition it resembles this in external physical appearance so closely that looking at specimens of these two rocks together it is difficult to distinguish them apart. .. It is in fact the most beautiful variety of Novaculite that can be imagined when taken dry and fresh out of the quarries about the middle of the east slope of the Hot Spring Ridge.David T. Day, Geological Reconnoissance Middle and Souther Counties Arkansas. Made during the years 1859 and 1860. p23

A later account by George Turner (1886) give us more detail on the use of this stone as an abrasive:

“The Arkansas stone is a very compact, bluish white, semi-translucent rock of uniform color and structure. The best, Washita, is less compact than the Arkansas stone, pure white and opaque. They are both composed of nearly pure, very fine-grained quartz, and differ from each other only in that the grains of quartz are finer and the spaces between them much smaller in the Arkansas than in the Washita stone.

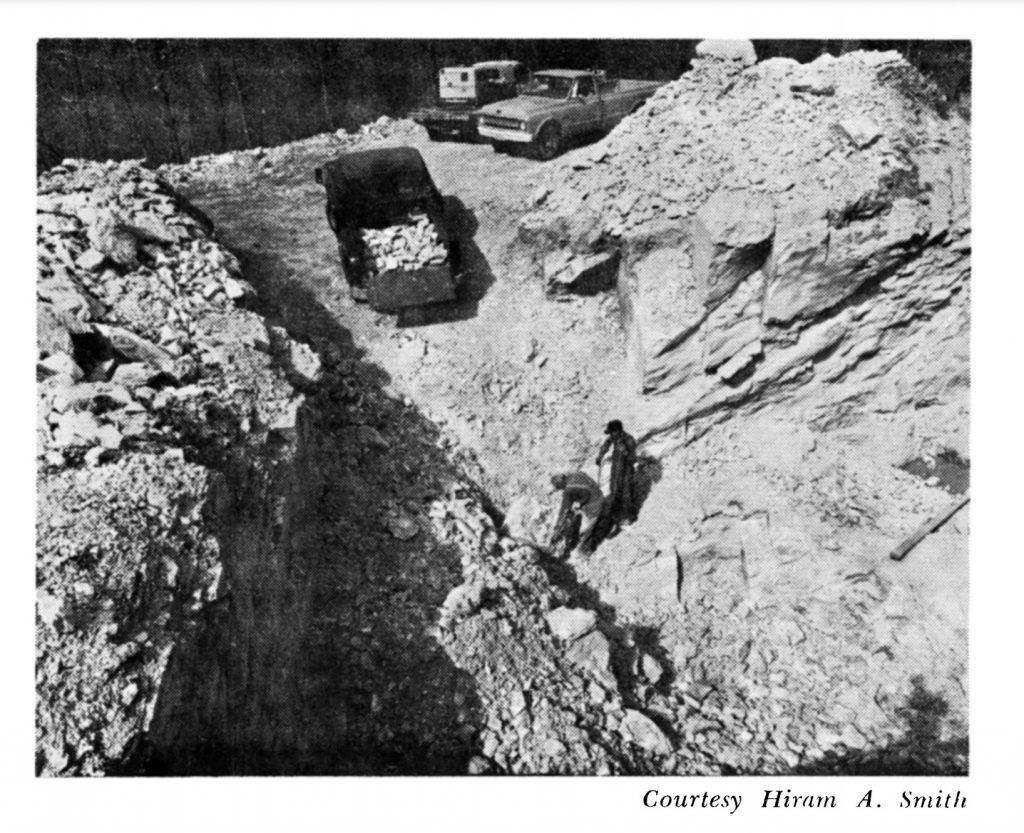

… Perfect whetstones of even grit, uniform in crystallization, and free from all impurities are found in only a few places, which are nearly always less than 100 feet in length, and are called pockets.

…Washita is shaped into blocks of from 100 to 2,500 pounds, and shipped to the various whetstone factories throughout the country.

…The stones are cut by means of saws. This method of preparing the stone for market is very slow, and hence the cost of the finished stone becomes greatly increased over that of the uncut. A gang of saws which will cut from 12 to 15 inches a day in marble will cut only about 4 inches in Washita and three-quarters of an inch of “Arkansas” stone. The rough Washita sells at the quarry at from 1 to 3 cents per pound, and the uncut “Arkansas” from 4 to 6 cents per pound. “Geologist, Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey, Washington, D. C., 1887

L S Griswold’s 1890 report explains that there are four companies working at that time with the facilitates needed to make finished whetstones (oilstones) and of these only the New York factories of Pike Manufacturing and George Chase are processing Washita stone. He describes the manufacturing process as follows:

Manufacture: The same machinery and methods are used in the manufacture of Ouachita as in that of Arkansas stone, though having a more perfect material to work with there is not much skill required in the laying of the stone in the gangbed, and being much cheaper than the Arkansas stone there is no necessity for such great care in saving fragments. As the stone is handled in larger quantity a regular system of sawing can be employed; thus the first cuts are two inches apart, the two inch slabs are cut in eight inch lengths and these into whetstones 1 ⅛ inches in thickness. The great mass of stone is manufactured in this shape all other forms of stone requiring special adjustment of the saws. After a careful sorting the stones go to the rub wheel. Office of the Geological Survey of Arkansas, Annual Report Vol III, 1890, p113

Manufacture

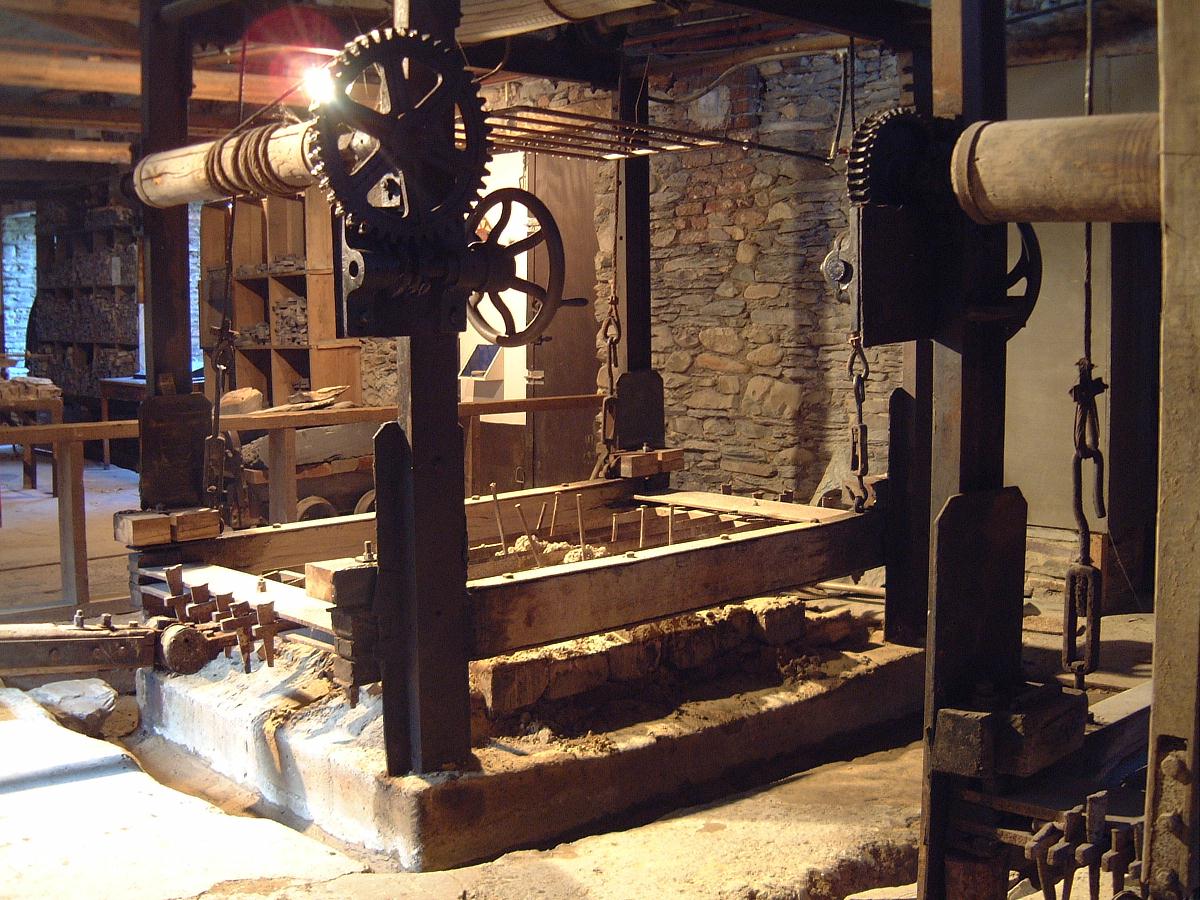

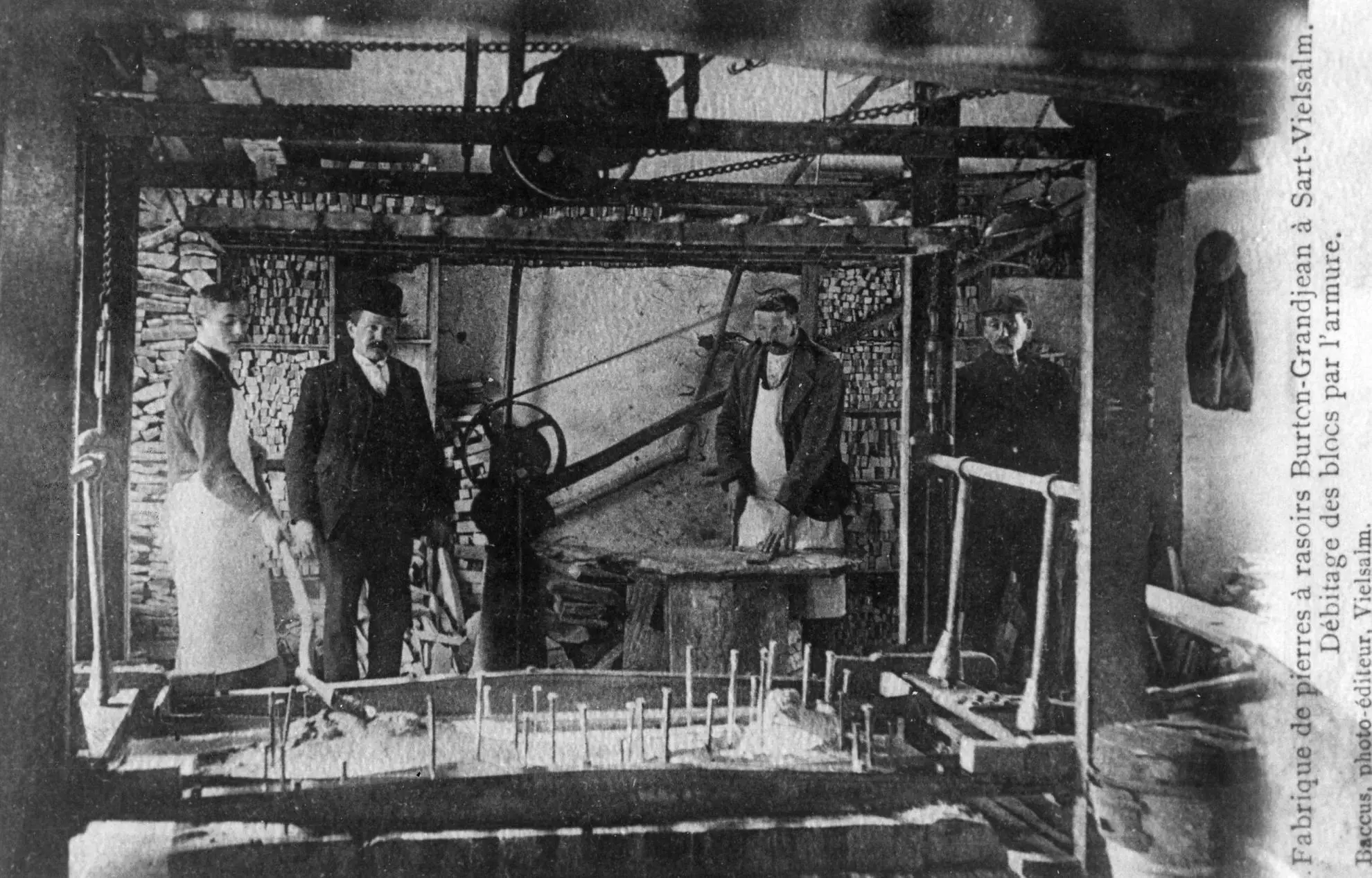

As described in the 1890 Geographical survey, the gang saws used to cut the oilstones consisted of a rectangular frame (typically 4′ x 6′) in which strips of iron about ⅛ inch in thickness and 3 inches wide are placed at the desired distances. This gang saw is suspended over the bed on which the stone to be sawed is placed and moved back and forth by machinery operated by horse, water or steam power. Sand is fed by hand to the saws and water is continually sprinkled from a pipe perforated with holes which extends across the bed above the stone and, trickling down, carries the sand to the saws and then washes out the fine powder produced in sawing. The sand grains fed to the saws become imbedded in the softer iron bands and, being much coarser than the grains of the stone, scratch them away.

The saws were kept steadily at work by a machine called a rope-and-chain gang saw. The gang is suspended by a single rope attached through chains to the four corners of the saw which passes over some wheels and is attached to a heavy weight at the other end. The gang saw is heavier than suspended weight and this causes a constant pressure to be applied to the work. The rate of cutting is determined by the speed of the saw and the hardness of the stone and this has the advantage of regulating itself to the character of the stone. This was useful in the whetstone business since it was generally not convenient to saw large homogenous blocks and instead many small blocks would be cemented together by plaster, meaning the saws would continually encounter material of different hardness.

A variation on the rope-and-chain machine is screw fed, where an operator controls the decent of the saws with a wheel. One of these machines survives and is on display in the Musée du Coticule in Vielsalm, Belgium:

You can see it working here:

You can see the process of laying out the stone fragments in this video of a whetstone manufacturer still operating in Belgium.

When making a traditional oilstone the first cuts are two inches apart, and then the two inch slabs are cut in eight-inch lengths and finally the stones are cut to one and one eight inches in thickness. The stones are then finished on a rub wheel:

The rub wheel consists of a cast iron disk about an inch in thickness revolving horizontally. A stationary framework is formed coming close down to the surface of the wheel and dividing the circle into several parts. Flat surfaces are ground by placing the stone on the wheel next to one of the arms of the framework and allowing the wheel bearing the sand to run underneath it, with the operator holding the stone against the wheel all the while.

The best oilstone

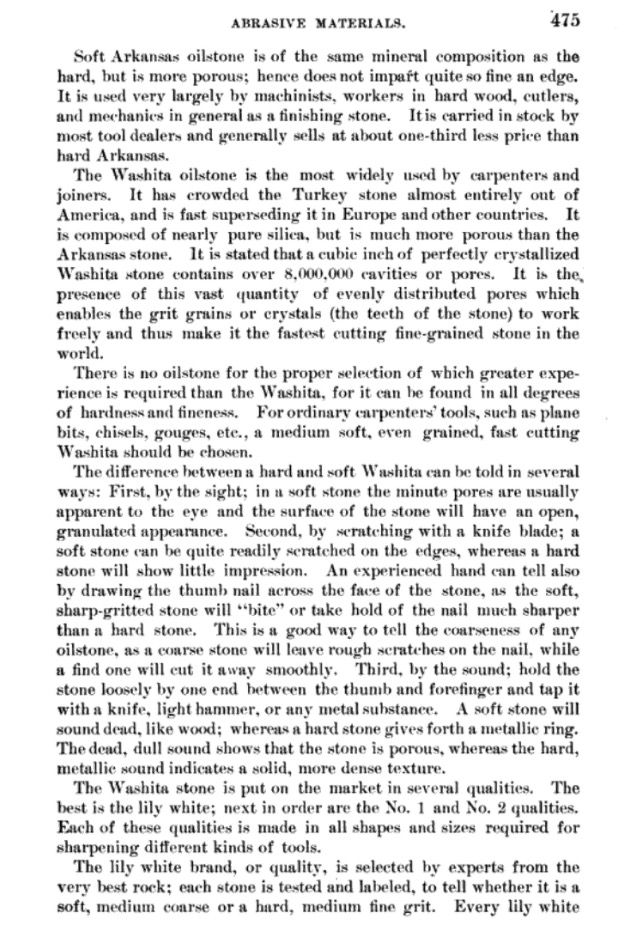

According to the geological reports Arkansas and Washita stones are 99.5% silica. Although the two stones closely resemble each other, the Arkansas stone is very fine grained, harder and is either white or bluey white and has a waxy lustre whereas Washita is less dense, more porous and has the dull look of unglazed porcelain.

The quarries where Arkansas stone was mined in the 19th century typically only yielded 25 % useable rock with the remainder being discarded as waste (compared to about 50% for Washita) with further waste incurred during manufacturing. This fact, combined with the relative difficulty cutting and finishing the denser Arkansas stone, was reflected in its retail price, with Arkanasas oilstones typically commanding twice the price of Washita. Happily these difficulties matched user demand, since the faster cutting Washita was more popular with general tool users.

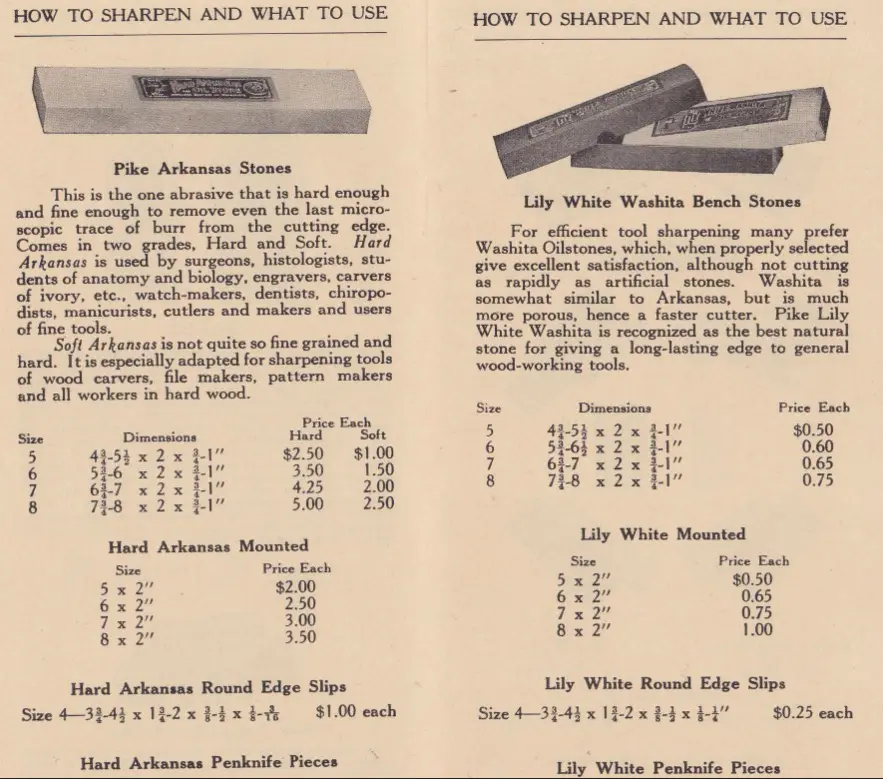

As can be seen from the account below, Arkansas was graded as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’, and Washita’s was classified as either Lily White, No 1 or No 2:

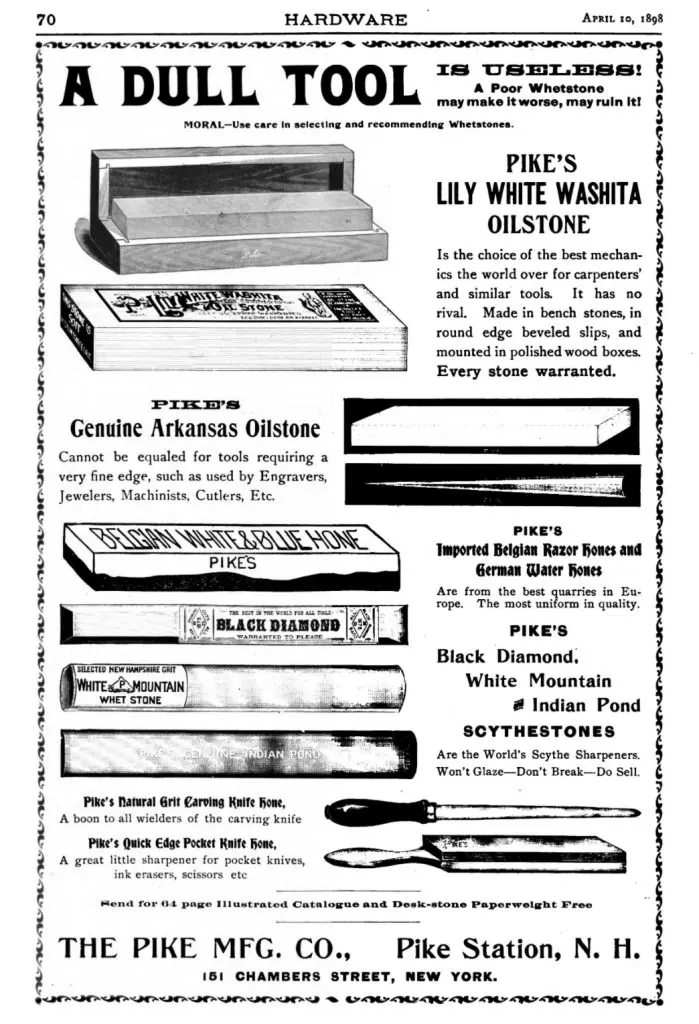

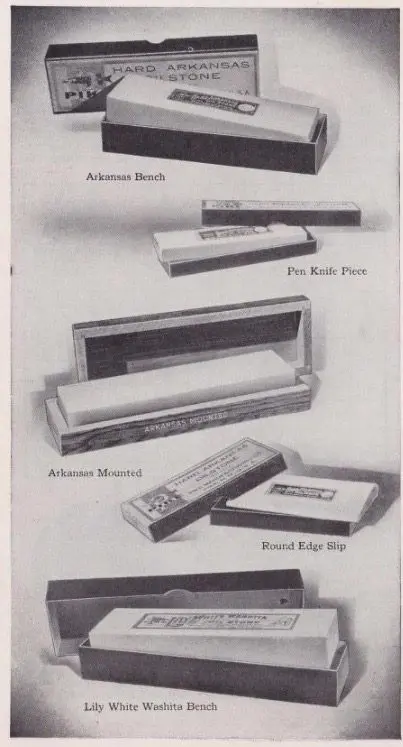

The two types of stone, Arkansas and Washita, had different properties. According to this 1905 ‘How to sharpen‘ pamphlet produced by Pike Manufacturing Company, who were the dominant producer at the end of the 19th Century, the hard Arkansas stone is particularly well suited to sharpening fine tools such as those used by engravers, watchmakers, surgeons etc and the soft Arkansas is slightly coarser and more often used as a finishing stone. Washita is the prefered choice for edge tools like chisels and plane blades.

Pike selected branded their stones according to their coarseness, hardness and quality:

The kind of edge imparted by these natural stones depends upon the size of the size of the grains (quartz crystals, in the case of these Novaculites) with large (coarse) grains cutting deep, far apart furrows such that the coarse stones tended to cut faster than fine grained stones but left a rougher edge. Pike also distinguishes degrees of hardness, with softer stones being more fast wearing than hard.

Of the three types of Washita, only the best – the Lily white – were graded, with the manufacturers distinguished two grades of hardness and fineness: Soft/Coarse and Hard/Fine. Pike recommended the fast cutting soft/coarse stones for carpenter’s tools such as plane irons, chisels etc with the hard/fine stones being reserved for narrow tools and pointed instruments which would otherwise quickly wear grooves in the stone.

The stones selected as ‘Lily White’ tended to be primarily white throughout, although the natural variations in colour has no bearing on the way the stones perform. Indeed at one point Pike created a range of stones with a red tinge they called ‘Rosy Red’ and these were sold as being the same quality as the lily white stones.

The No 1 Washita stones were not graded but were selected so as to be free from noticeable imperfections and the No 2 was a lower quality stone with at least one good face but containing cracks or other imperfections – such as streaks of hard quartz of soft ‘sand holes’ – on other faces.

The Pike pamphlet also says that the Washita No 1s were the best sellers so presumably the actual variation in cutting capabilities from the quarried No 1 stone - compared to the graded Lily Whites - was not so great in practice as to deter the purchasers from buying this slightly cheaper option.

According to Pike you can tell a soft stone as follows:

“in a soft stone the minute pores are usually apparent to the eye, and the surface of the stone will have an open, granulated appearance; second, by scratching with a knife blade, as a soft stone can quite readily be scratched on the edges,… third, by the sound, holding the stone loosely by one end between the thumb and forefinger, and tapping it with a knife, light hammer, or any metal substance; the soft stone will sound dead like wood whereas a hard stone gives forth a metallic ring.”Pike Oilstones: How to Select and Use Them (1905)

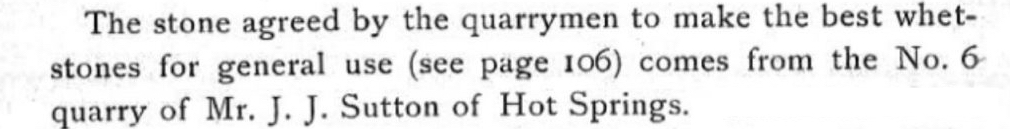

The 1890 survey quoted above, says the finest material to make whetstones was obtained from one of J J Sutton’s Indian Mountain quarries:

Sutton is the author of several articles about Novaculite stone in Geographical tomes around this time, so possibly there is a bit of marketing behind this claim, but it does seem that the other notable quarries are all close by in this area, including Barne’s Big Quarry, which is also on Indian Mountain.

The rough location of the Washita quarries is shown below:

International Success

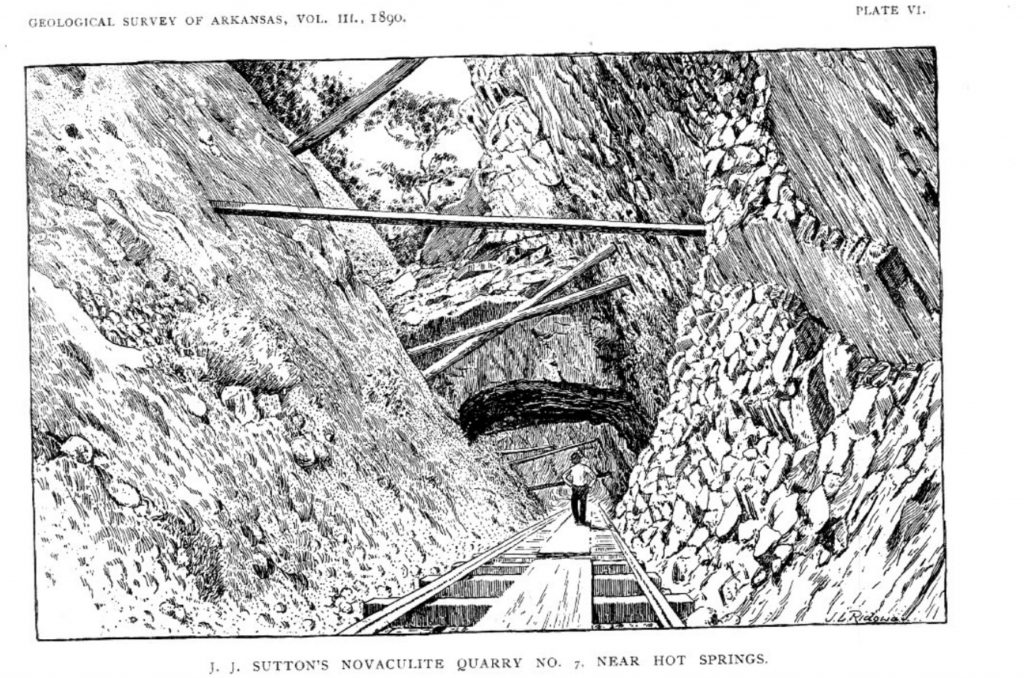

The 1890 report tells us that by the mid 1880s significant numbers of Washita oilstones were being exported to England, Germany, France, Canada and Australia; with exports representing ¼ of total production.

Tradesmen in countries like the UK were used to far less effective oilstones at this time, so the arrival of these excellent new stones from America made a big impact, as explained by Walter Rose in his book The Village Carpenter:

Of all modern appliances, I regard the modern oilstones as the most beneficial to woodworkers of the present time. In my youth we did not, of course, realise it, but now I see how very much we were handicapped by the poor class of stones then available. A few men were the possessors of a “Turkey”; the only other variety known to us was the “Charnley Forest”. Both were natural products, for a manufactured stone at that time had not been heard of. The Turkey, a cream and brown mottled stone of beautiful smooth texture, can still hold its own, and it may safely be predicted that, in the rare instances where pieces still remain, they will, by virtue of their merit, be handed down for use by succeeding generations. I never saw a full-sized Turkey stone without minute cracks and fissures. Apparently it was obtained from the natural rock with difficulty; the sides were uneven, and we assumed that the producers were content with attaining one flat side. Turkey stones absolutely needed the protection of a wooden case, imbedded in which they were good for lifelong use. But the owners were careful of them, lest they should fall and be shattered.

All my father’s men used the “Charnley Forest”, a natural British stone resembling slate, and I have vivid memories of the incessant rubbing that was necessary before a keen edge on the tool could be obtained on them. They varied slightly in quality, but even the very best were dreadfully slow; and all demanded an abnormal amount of labour, to lighten which we sometimes applied fine emery powder to the surface. This quickened the process, but left a raw and unsatisfactory edge to the tool. Recourse to the grindstone was had immediately the sharpening bevel became wide. In the year 1889 the “Washita”. An imported stone, appeared on the English market, and was hailed with delight by all woodworkers , who straightway discarded their “Charnley Forests” for ever. One old stone, that had till then been considered of supreme merit and priceless value, was then hawked round the workshop where I was serving a term of apprenticeship, and failed to find a purchaser at the proffered price of sixpence. On my weekend visits home, I carried a new stone to show my brother, who insisted on keeping it. It created a minor sensation in my father’s workshop, where its undreamed of quality of sharpening captivated all my father’s men, each of whom speedily obtained one. Being a natural stone, it varies in quality. If quick cutting is required to ordinary carpenters’ tools a coarse grained one should be selected, but for carving tools a fine texture is preferable.

Since that time, two manufactured stones have appeared. The “Indiana” and the “Carborundum”. Each is made in three grades, fine, medium, and coarse, and each has recognised valuable qualities. Experience of work at the bench. Inclines me to favour the fine “Indiana” as a stone of a texture on which a smooth keen edge can be obtained. But for ordinary outdoor carpentry I would prefer the medium.Walter Rose “The Village Carpenter” 1937

A James Howarth catalogue from around the time that Walter Rose’s recounts shows that Washita stones were 3 x the price of the old Charnley Forests:

The fact that the significant extra cost appeared to be no deterrent to potential purchasers is an indication of just how much of an improvement the new Washita stones were.

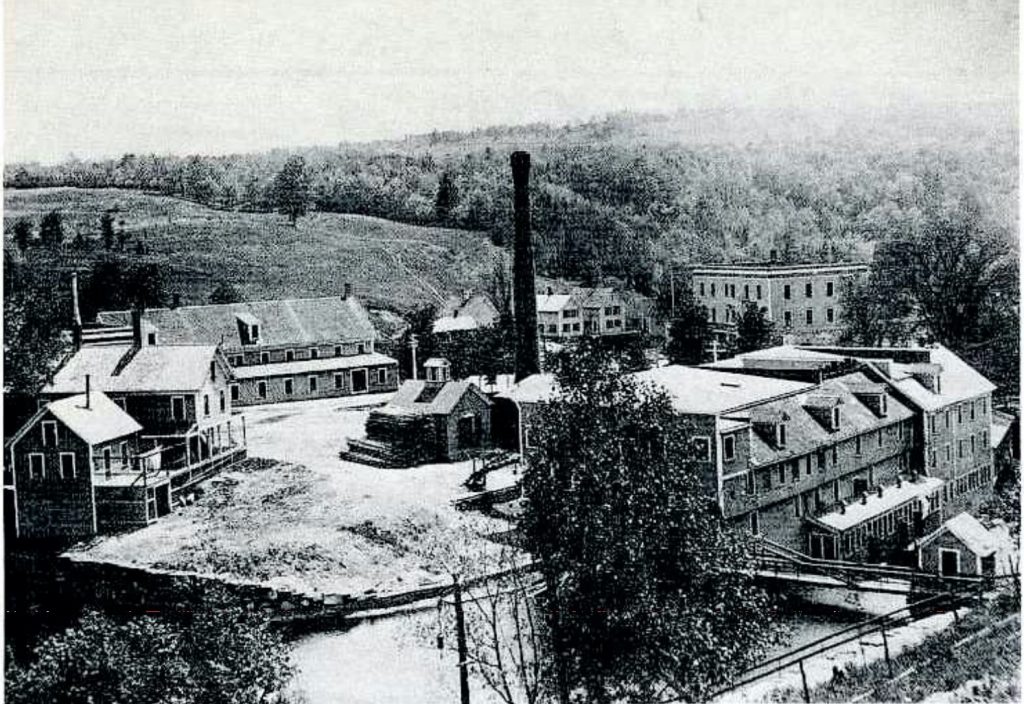

Pike Manufacturing

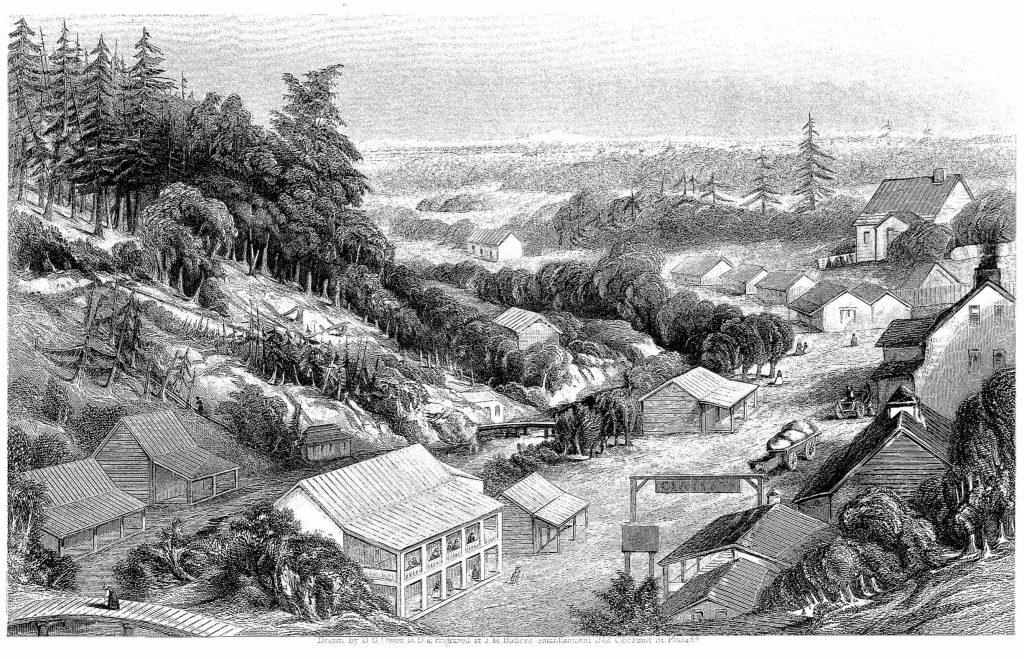

The 1905 Pike pamphlet claims that Pike Mfg Co ‘for the past few years’ has controlled the output of the best Washita and Arkinsas quarries. In 1891 they had bought out the Chase brothers who, according to the Geological Survey, had been making and selling Arkansas oilstones since the late 1840s; and then went on to buy Sutton’s quarries, as can be seen from the nearly identical etching of Sutton’s no 7 quarry (see above) included in their advertising:

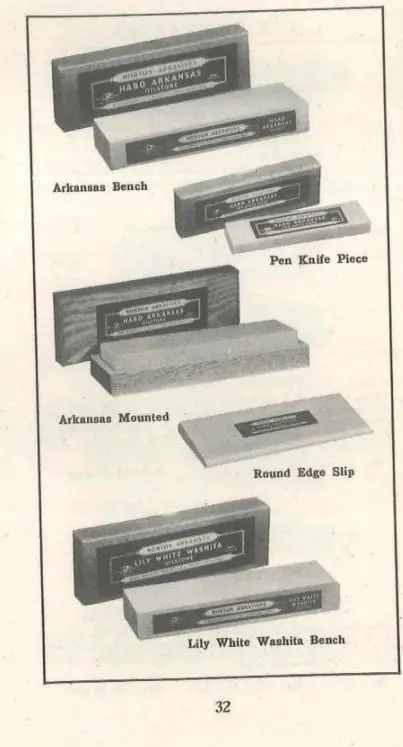

Norton

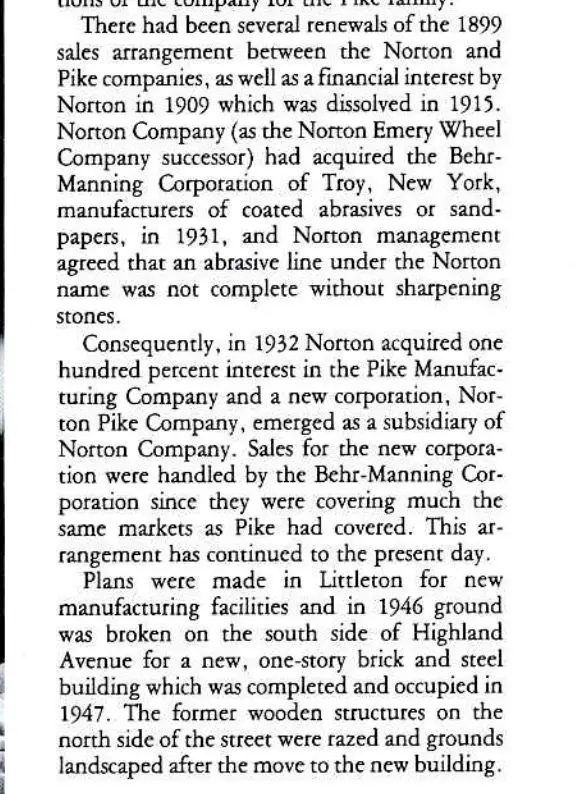

Norton introduced the first manmade sharpening stone in 1897, the famous India stone that is still made today, and Pike – keenly aware of the limited room in the market for competitors, remarking as he did in a letter to Norton that ‘One stone usually lasts a man a lifetime. There are only a few oilstones bought‘ – sought out a partnership and were made sole agents for the new India stones in 1899.

in 1932 Norton completed its acquisition in the Pike Manufacturing Company, creating a new subsidiary, Norton Pike, with another acquired business (the Behr Manning Corporation) managing the sales side of things:

Modern Revival

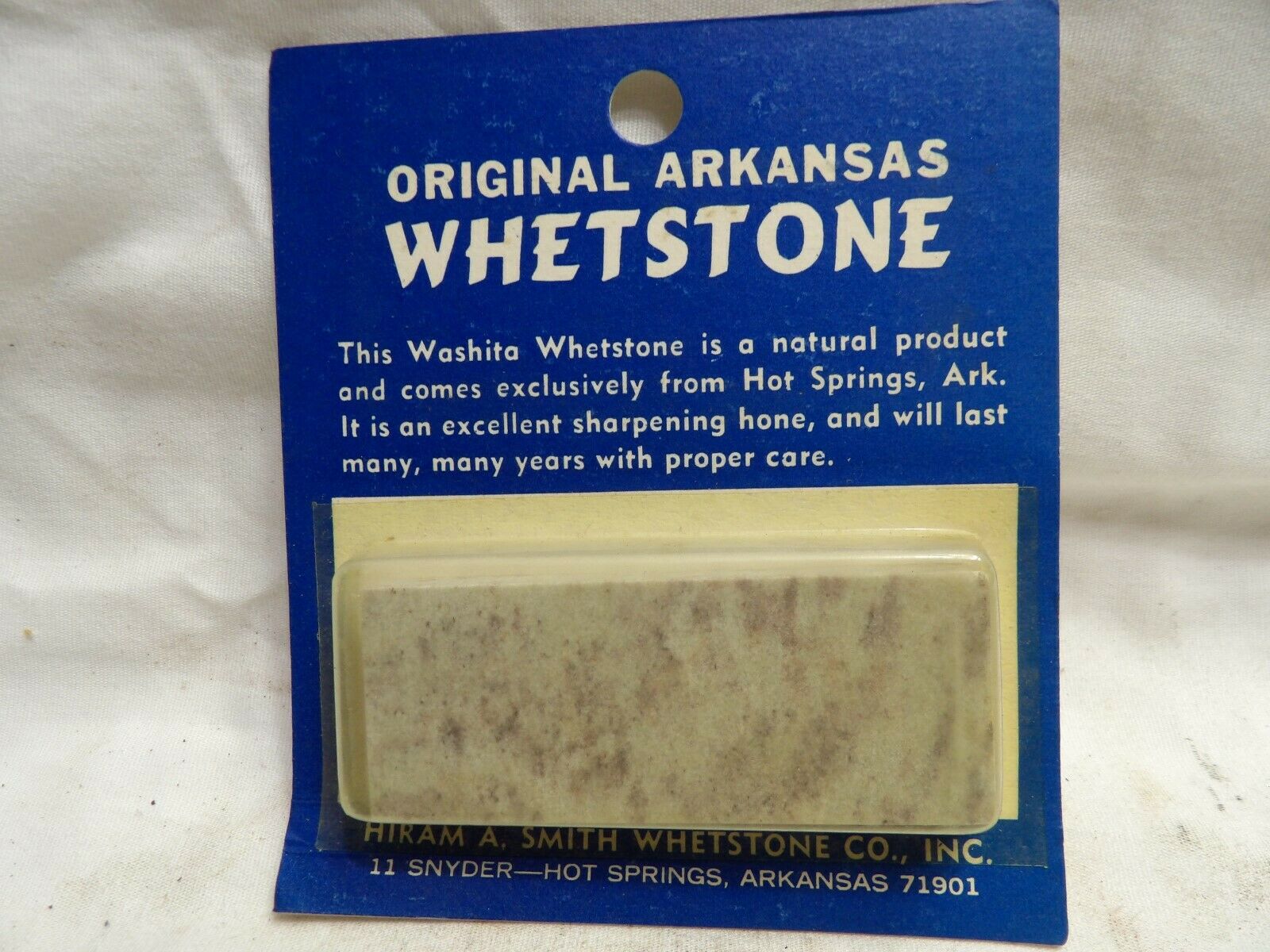

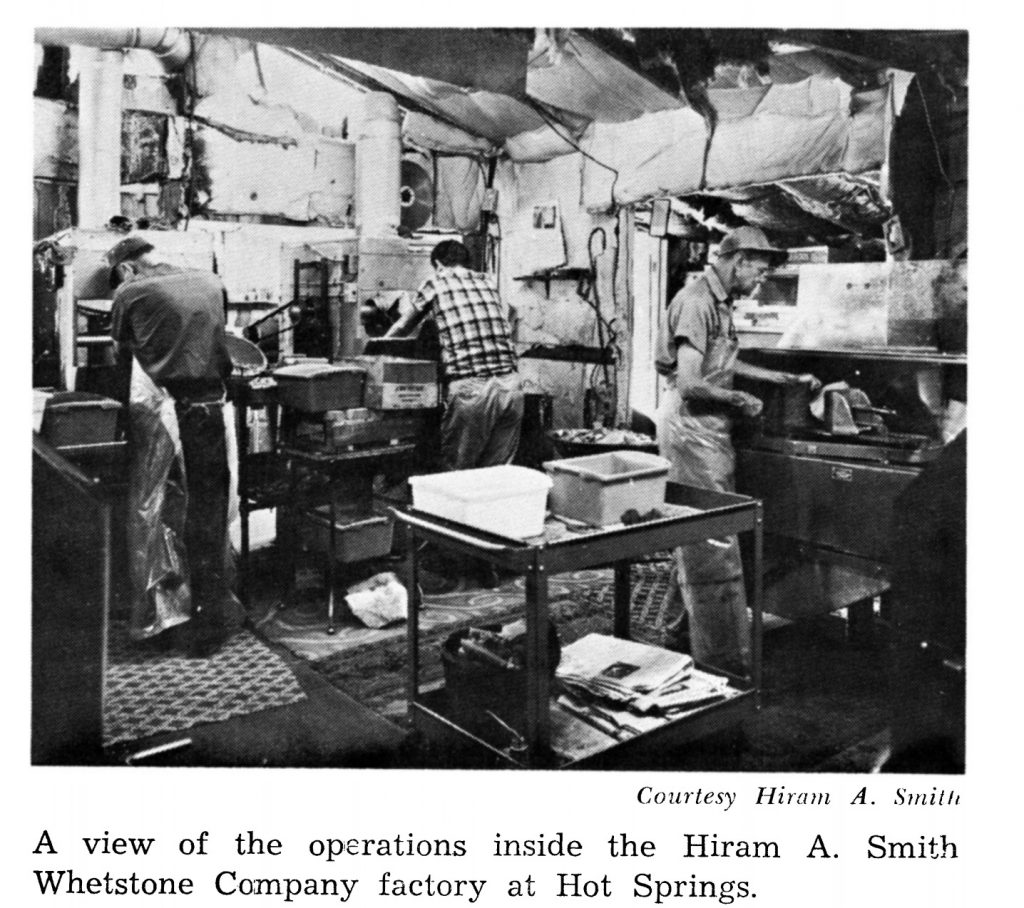

In 1962 Hiram A Smith established a whetstone processing plant near Hot Springs and at one point claimed to be the largest Novaculite whetstone producer in the USA. Sadly the Smith Whetstone business no longer appears to be trading.

Norton still own their Novaculite mines in AR but, after a short lived stint producing lily whites for Tools for Working Wood in the early 2000s, have decided it is no longer economically viable to produce Washita stones.

Dan’s Whetstones was established in 1976 near Hot Springs and the owner – Dan Kirschman – controls several quarries that supply various grades of Novaculite. Unusually, their stones are cut and finished individually, as would have been done in the days of Pike Manufacturing Company.

Although Dan specialises in Arkansas stones he makes a limited number of Washita stones available, which he describes as a coarse, soft stone of relatively low density, in line with the classifications of old.

Here is my Washita stone. Odd to think that the oldest thing in your workshop, by about 400 million years, is a piece of stone from a small mountain just outside Hot Springs, Arizona

References

| 1⏎ | Norton literature from the 1930s no longer mentions Hot Springs, referring instead just to the Ozark mountains. Although modern maps tend to identify Ouachita as a separate range, Schoolcraft says that geologically the Hot Springs area can be considered the southern termination of the Ozark chain of mountains |

|---|